Introducing Psychedelic Projection

First a little intro to Peter Wynne Wilson who invented and produced many of the early projection effects, and we thank him for that. Sid Fossil is currently a partner with Peter Wynne Willson, who was Syd era Floyd projection artist, formed L.M.C (light machine co.), invented Splodascope, total eclipse, prism rotators, and supplied Opti, etc. Later in time Pete formed WWG with Tony Gottelier, fitting out discos, product design, etc, sadly Tony passed away 15 or 20 years ago.

Pete was all set to retire but Sid intervened (being some 20 yrs younger), and have been purchasing kit and upscaling and refining effects over the last decade, occasionally do shows with Opti Neil (Rice) and others...Liquid light orchestra

Sid and Peter can now be found at Fossiloptical Ltd

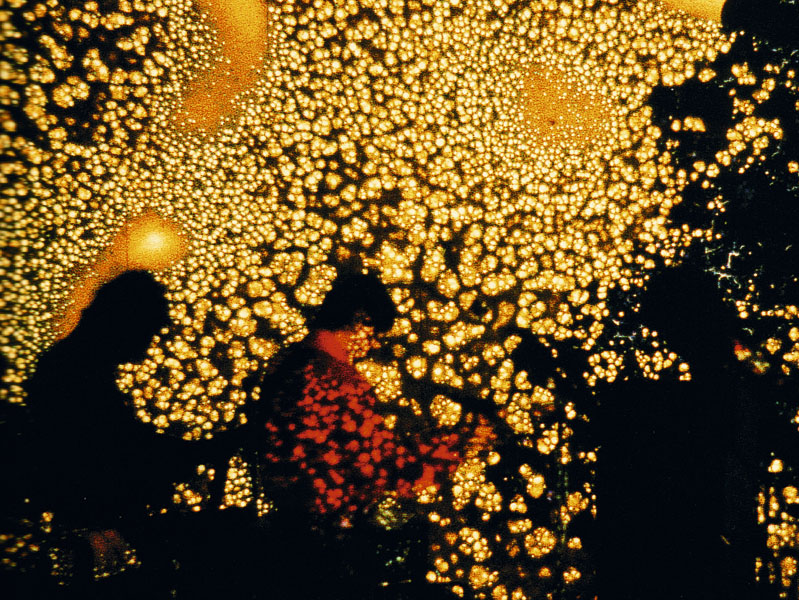

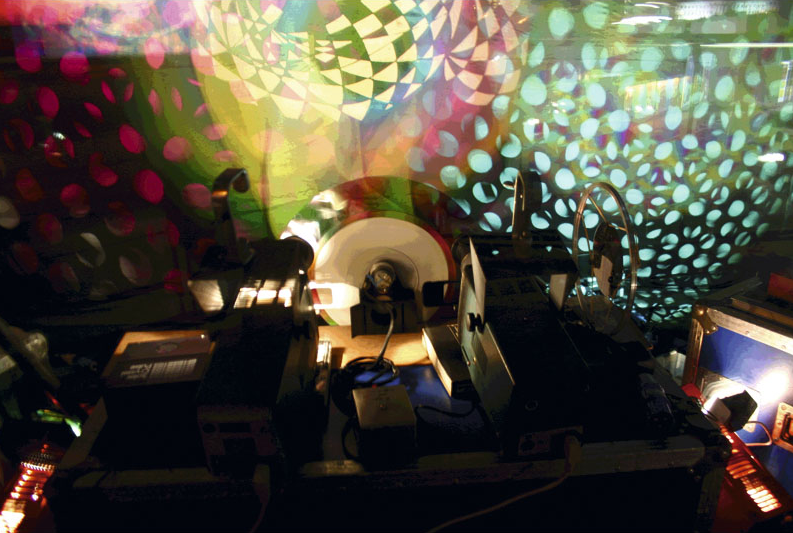

Fossiloptical have a mainly liquid lightshow with Pani large format slide projectors, up to 150,000 lumen output, loads of them, based in Oxfordshire,UK and can make the unthinkable happen!

View the website [click] (you must) or check in on facebook [click]

And as you will read later, we thank Neil Rice and Star Trek for the 3" cassette.

What follows is an extract from theTPI Magazine and details some of the facts on the history of this entertainment media. The magazine can be subscribed to and has social media links and a wide distribution.

These articles were written by a great journalist, Jerry Gilbert. Jerry not only knows his stuff, but his writing conveys a story rather than just cold facts. It is with many thanks to Jerry these articles are reproduced here. To know a liitle more about Jerry, click here. Read many of his wonderful articles, great stuff!

Thanks are also due to Neil Rice for his assistance in bringing some of this content and many other submissions to be found on the Karillon2 website, as well as much technical information.

Total Production International

Founded in 1998, Total Production International (TPi) magazine is widely regarded as the industry’s most authoritative monthly business-to-business publication dedicated to the design and technology of live events, from concert, gig and festival productions, to theatre shows and temporary events. Jerry Gilbert was the editor at the time of these articles and produced a much loved and thoroughly read magazine.

Psychedelic Projection

TPI December 2008 Issue 112

|

The people, technology and events that shaped the modern Live Entertainment Production industry, by Jerry Gilbert.

The era of psychedelic lighting — between 1965-68 — is redolent with the whiff of joss sticks, patchouli oil and Acapulco Gold, copies of the I-Ching, The Dice Man, The Whole Earth Catalogue and countless existentialist novels. Also de rigueur in every bedsit was the obligatory Oriental board game ‘Go’ — which requires at least two lifetimes to master.

Projected light had grown up alongside psychedelic music imported from the American west coast in the mid-to-late ’60s, and the concurrent home-grown British progressive rock movement.

The means of projecting a range of psychedelic, hallucinogenic lighting, erotica and mandalas, was at the very core of epidiascopic lighting.

The legacy of oil wheel and slide projection quickly found its way into the artillery of the mobile DJ, and pioneers of some of the great progressive rock shows of the late ’60s and early ’70s were suddenly given a new lease of life by the onset of the discotheque industry.

Although there were many practitioners, three people stand out as bridging the psychedelic era: Peter Wynne Willson, Neil Rice and John Lethbridge.

Across the Atlantic, however, the technique employed was somewhat different from the UK: rather than boiling liquids in slide projectors early American exponents preferred using liquids in clock face bowls, nestling on overhead projectors.

|

In 1994, the two proto-techniques merged — along with the best of ’90s technology — in a celebration of the ’60s lightshows at the LDI Convention in Reno. Promoted by High End Systems as a vehicle to launch Cyberlight, this was a timely opportunity for HES co-founder Lowell Fowler to take a fond look back.

|

|

The basic projector blueprint — a condenser optical system comprising mirror, lamp, primary condenser, heat filter, secondary condenser and focusing lens — set the design formula for a creative wave of early experimentation and customisation. (shown is the Aldis Tutor projector)

There was an explosion of lightshows, some featuring frontiersmen who are still around today. Some of the more notable included Cyberdescence and Crab Nebula (founded by Pat Chapman — who later started Entec at the Marquee Club, and became an acknowledged, published expert on curry) — Acidica and Alpha Centauri (now better known as A.C. Entertainment Technologies Ltd).

They were even joined by some of their American brethren. The link was made when Joe’s Lights and The Joshua Lightshow, residents at Fillmore East in New York, crossed the Atlantic in the early 1970s to perform at new rock venues, the Rainbow Theatre in Finsbury Park and Rank Leisure’s bold new Sundown Theatre experiment — converted cinemas in heavily-populated suburban areas of London — masterminded by the seminal influence of the great entrepreneur, John Conlan, that persists to this day.

The belt and braces art of the early pioneers created an idiom that modern industry, for all its sophistication, just cannot lose its love affair with.

Welcome to the projection revolution of the ’70s.

PETER WYNNE WILLSON:

A WHEEL TURNS FULL CIRCLE

In 1994 — the same year as the High End Systems extravaganza — Peter Wynne Willson was reunited with Pink Floyd for their ground-breaking Division Bell world tour. Brought in by LD Marc Brickman, he modified the show first used to light the band nearly 30 years previously.

“The strongest link between the two eras was the liquids,” remembers Wynne Willson. “The Floyd tour managed to bridge the gap between the 250W projections of the ’60s and 7kW Xenon projection in massive stadia in the ’90s.

“Also, the liquid techniques used on the tour, including a version of clock glass and pumped liquid slides, were very similar. The 7kW Telejector was adapted by Wynne Willson Gottelier [WWG] to convert into an overhead during the gig, for the clock glass type effects, just as in the days of yore with the Aldis Tutors. For the operator, a female, it was like working over a hot stove!” The set also included four ‘Daleks’, specially-devised by WWG (see later).

It is no coincidence that the Floyd’s original madcap frontman, Syd Barrett, wrote ‘Astronomy Domine’ (the subject of Wynne Willson’s lighting regeneration on that tour) while living in the latter’s flat in London’s Cambridge Circus, or that Pink Floyd’s production manager, Robbie Williams, had also flirted with the equally legendary Krishna Lights, the first organised disseminators of projected lighting and effects back in the 1960s. And so a gap spanning nearly three decades was bridged.

Wynne Willson started life in pure theatre, amid a sea of Strand Pattern 49s, groundrows and footlights, rheostat dimmers and twin preset desks. His first projectors were adapted from theatre lights. “After working in provincial theatre I arrived at the New Theatre (now the Albery) and anything they chucked out I rehashed.”

Later, as The Pink Floyd’s lighting designer, he was initially using flashing spots for projection at places like the Roundhouse in Chalk Farm, but this soon made way for projected patterns derived from both liquids and polarising effects.

He remembers: “I used to use little spots with Pattern 23-style optics in four groups of four as footlights with Floyd; they had a very fast rise time and a nice focusing system.”

His three-floor flat in Cambridge Circus became something of a cultural hub, with the tenants heavily influenced by the Oriental cults and religions so popular at the time. And when Syd Barrett moved in (remaining there for a year or so) he was the catalyst in bringing Wynne Willson on board with his band.

Wynne Willson’s peers at the time were performance artist/photographer Mark Boyle’s Sensual Laboratory, which worked extensively with Soft Machine, and Joe Gannon, who had emerged from the cultural melting pot of W11.

Although UFO in Tottenham Court Road was the nearest place to a residency, during 1967 Floyd gave numerous performances at leading European venues before touring America — and the UK in following year — with the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

“UFO was undoubtedly the proving ground of the psychedelic lightshows and Mark Boyle did a lot of fabulous work there,” recalls Wynne Willson.

Another lodger at Cambridge Circus was Jimmy Doody, who founded the seminal Krishna Lights in 1968, which commercialised psychedelic lighting. Also on board at Krishna was Keith Canadine, who later became one of the co-founders of Optikinetics.

“Jimmy lived under the bench of my workshop for a while — he was interested in material you could sell because everything to that date had been wet, and so he started sealing slides. I remember I had done an acrylic liquid wheel at a gig at the Marquee Club but it wasn’t sealed... you put the liquid in and it was the meniscus that would stop it from running out. But I think it was Jimmy who developed the sealed liquid wheel, and took out a patent which he later licensed or sold to Optikinetics.”

But Wynne Willson’s stint with Floyd was driven by the opportunity to produce live lightshows. He remembers: “I provided liquid projection, colour effects, flashing spots, polaroid projections, and injected liquid effects, quite different from sealed slides/wheels.”

His contract with Floyd was £20 a week and 5% of the gross. The early gigs were all around London — Eel Pie Island in Twickenham, The Roundhouse, UFO and various art colleges. “And that’s where it started to expand,” says Wynne Willson.

“We would travel further afield when the Brian Morrison Agency started booking the band. There was a little tour of the States that hit the West Coast, which was staggering. We played in Los Angeles and at the Winterland in San Francisco with Janis Joplin and Procol Harum. There was a resident lightshow with enough kit to cover the walls of the auditorium with projections.”

CLOCK-WATCHING

It was at Fillmore West that Wynne Willson first saw the clock glass type liquid rather than the three-layer liquid slides. “The effect was more wobbly; you didn’t get the detail of the liquid slides but you got a very dynamic effect complementary to the music.”

But he was never a fan of the clock glass effect. “At that time the overhead projectors were rubbish — very watery in an optical sense,” he remembers.

Instead, he was inspired to manufacture a high-intensity, miniature version that could be used on an upturned Rank Aldis projector for his overhead effects, using a deflecting mirror to give a sharp and relatively powerful image.

“I used this with Cream at [Brian Epstein’s] Saville Theatre in Shaftesbury Avenue. There were several well-known bands appearing so I wanted to do something different — and the objective lens was far superior to that of a conventional overhead.”

Wynne Willson’s experiences of doctoring the famous Rank Tutor 1 and Tutor 2 projectors are similar to those of his peers. The original 1kW Aldis projector had a cast base and fabricated top, and the Rank version was almost identical. Then Rank took over Aldis, producing the Tutor I, which was all die-cast, and using the same lens system — but with square, not round heat filters.

“We would usually take these out to cook the slide,” adds Wynne Willson. The original Aldis also had two slide bars for the slide and lens carriers which Rank retained, providing long-throw lenses of 150mm, 200mm and 300mm.

“I used the very long ones to create a mirror effect, comprising a perforated strip [like a gobo strip]. The projector would be set sideways and to the end I would clamp a frame with a suspended mirror — you could strum the mirror in order to get Lissajous patterns from the effect you put into the gate.

“Using various slots, you could create a wonderful 3D effect, and the beauty of having mirrors suspended is that they would act as an

unbelievably fast followspot, quite different from the open carbon arc ‘Sunspots’ I’d handled at the Royal Albert Hall with a slew of bands.”

Neither was Wynne Willson a lover of stroboscopic lighting — that stridently disorienting effect that came to prominence at the same time. Xenon tubes had been around from early on but his first strobe was neon, an ex-military Westinghouse device.

Evidence of this is in the aforementioned four Daleks, devised by WWG, producing disorientating, visible beat oscillations from 4kW HMI sources, with a special giant colour generator produced by WWG using High End Systems’ dichroic coated borosilicate. It was a far cry from the 150W and 250W projectors which had marked the beginning of the idiom.

“This was huge,” says Wynne Willson. “Since essentially I didn’t like the aggressive nature of the strobe, I developed a high-speed colour mixing system, with twin colour wheels which could be rotated at speeds far beyond the persistence of vision.

“The initial illusion was of white light which produced rainbow trails behind any movement, because your eyes couldn’t resolve the coloured light fast enough. In the brain, however, all sorts of colours and form would appear — thus you could have some really good hallucinations without experiencing the violent nature of strobes.”

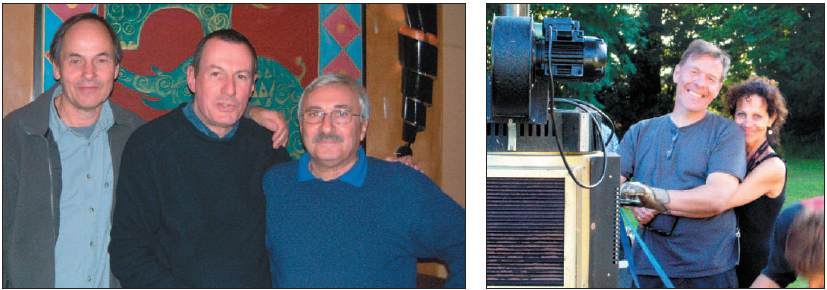

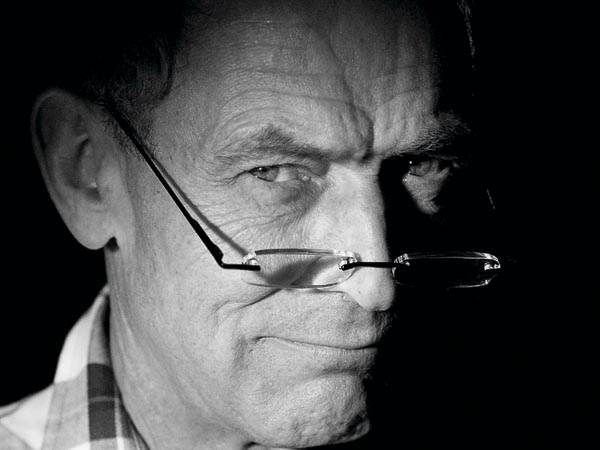

Below: A Krishna Lights reunion(left) and (right) Peter Wynne-Willson today, with partner Cathy, rigging a 6kW projector.

Wynne Willson had stopped touring with The Pink Floyd by the time he was asked to light a special, one-off show for them at The Roundhouse in 1968. “We had six projectors with long lenses [one person could operate two] and did the whole show with mirrors [as described above]. My eyes were popping.

“We combined this movement with high-speed colour wheels which, because of the speed in that situation would produce spectrum colours. Integrated with that we used high-speed flicker wheels which would chop the beam, so you would get two or four little sequences, spectrum painted, which looked like little spectral worms.

“With a simple lens I could project a badly-aberrated filament on the screen that could be manipulated to produce convoluted folded images — which needed careful handling — but without objective lens.”

MOONLIGHTING

By 1968, Wynne Willson had formed his first company, Moonlight and Son, who provided the lighting for a Pink Floyd film on Barnes Common — part of BBC2’s ‘The Sound of Change’ broadcast — where he had to conform to something other than rock’n’roll sensibilities.

“I was using Mole Richardson followspots, which were extremely hot, and all our effects were frying.” His solution was to build water tanks into the gates, and suspend the gobos and rotating wheels in the tanks.

In order to conform with Granada Television’s standards when asked to do a live TV spectacular for The Move, they also had to rewire all their spots with modern cannon connectors (kindly donated by the studio).

Wynne Willson started to get into commercial design in a big way and by 1972-73 was making attachments for Optikinetics. “By 1974, I was producing acrylic lighting devices in earnest, such as prisms, prism rotators, mirrors, splodascopes... and the Total Eclipse.”

This effect was based on a child’s spinning top and was purpose-designed for companies such as Optikinetics, Illusion and Meteor Lighting. It was a device with four wheels in the gate to create a dynamic bullseye, and they were made by the thousand.

Later, Wynne Willson was equally prolific after forming the Light Machine Company, subsequently joined by John Richards, where they made all manner of frame attachments and their own fabled Light Machine Gun, a narrow, hard-edged beam projector.

There was also the stand-alone Rainbow; a high-speed colour unit, the effect is described above but it was now generated from dichroics

obtained from Thorn Electric — “a by-product of their ‘Cool-Ray’ PAR 38 production”.

Today, WWG — which Wynne Willson formed with the late Tony Gottelier — remains in the forefront of invention to this day. But as far as projection is concerned, back in 1994, in an aircraft hangar in LA, and in one of the largest productions of all-time (The Division Bell), the wheel literally turned full circle.

[Sid Fossil is currently a business partner with Peter Wynne Willson,, who was Syd era Floyd projection artist, formed L.M.C (light machine co.), invented Splodascope, total eclipse, prism rotators, supplied Opti, etc.

They now have a mainly liquid lightshow with Pani large format slide projectors, up to 150,000 lumen output, loads of them, based in Oxfordshire, can make the unthinkable happen! The website is Fossiloptical Ltd ]

TPi

Photography courtesy of

Neil Rice, David Fowler.

Peter Wynne Willson and Andrew Whittuck

NEXT MONTH: More psychedelic happenings with John Lethbridge and co.

Psychedelic Projection & the age of enlightenment

Part 2

The people, the technology and the events that shaped the modern live entertainment production industry

by Jerry Gilbert

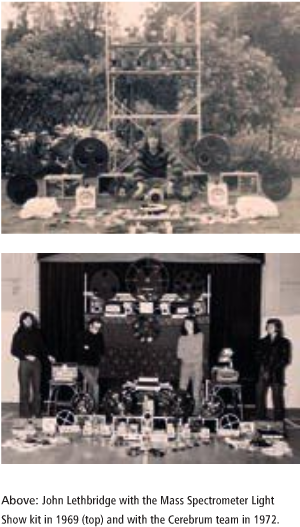

| JOHN LETHBRIDGE: Reliving The Technicolour Dream In March 1969, two land survey draughtsmen working at County Hall in Kingston, with a shared interest in underground music, decided to form a light show. Equipped with a converted Hanimex slide projector, a few bottles of ink and a strobe — essentially, a cardboard disk tied to a food mixer — which could be held in front of the projector, John Lethbridge and Pete Samuel went into business as The Mass Spectrometer Light Show. After earning a total of £6 from the first five gigs — their debut was with Van Der Graaf Generator at a school in Crawley — things gradually improved, and by October they had a twice-a-week residency at the legendary Eel Pie Island in Twickenham. By the end of their first year they had produced 51 light shows, working with such bands as Genesis, Mott The Hoople, Hawkwind and Small Faces. They had also met up with Mark Hancock, a DJ specialising in society parties, and before long were travelling up and down the country at weekends turning on debs to the novelty of ‘psychedelic lighting’. In the following May, having become disillusioned with office work and given up his job, Lethbridge decided to haul himself off the dole by advertising a strobe in Melody Maker which he had built from a kit offered in an electronics magazine. The response was amazing — he quickly cashed in his savings of £40, bought two more strobe kits and realised he had the potential to start a business. On July 4 1970, Cerebrum Lights made its first appearance at an open-air pop festival at Portsmouth Stadium. The strobes started selling at a regular rate and Lethbridge decided to market a couple of custom-built projection effects, which he had designed for the light show. |

|

Among his early customers were Paul Woodhouse (later to become a director of ICElectrics), Todd Wells and Dave Street of Soundout (now DiGiCo/Soundtracs), and Tony Gottelier.

Lethbridge remembers: “Meeting Tony proved to be one of the big breaks, as one of the guys in Tony’s disco had designed a sound-to-light unit that he wanted to sell via Cerebrum.

“Also, Tony had recently met a young light artist called Phil Brunker, who was making 6” liquid wheels which he fitted to converted slide projectors. Phil, apparently, was also without a marketing outlet, and as Tony had a full-time job he offered to put a proper display ad in the music press if I was prepared to deal with all the enquiries for these new effects.”

Meanwhile, the light show was becoming better equipped and now had several projectors, including an old Aldis 500W Tutor, some brand new Tutor 2s, an overhead projector, in which they projected live insects and newts, as well as oils, 8mm cine, strobes, UV, a home-made flashing footlight system for onstage use and over 1,000 special slides.

The main effect was still created by boiling special inks in the projector gate, but new ideas were essential as competition was hotting up.

COMPETITION

Several rival lightshows were operating in the Surrey area, including Crystalleum Lights, run by a blonde-haired, bespectacled hippy called Martin Blake, and Infusoria Five Acre Light Show, run by Neil Rice.

Fortunately, four of John’s friends had become social secretaries at various colleges and Mark Hancock was now a director of Juliana’s Discotheques. “So it was not unusual to be working with Pink Floyd at a Midlands university one night and the next at Lord Somebody-or-other’s country mansion, lighting a debs’ coming out party.”

By now, Lethbridge was besieged with enquiries. One was for an entire club installation at a new disco called Bumpers, which led to the setting up of Meteor Illusion by Tony Gottelier and John Jeffcote, while Phil Brunker teamed up with Neil Rice and Keith Canadine from Krishna Lights to form Optikinetics.

Meteor Illusion was soon doing good business and became the first company to offer Cerebrum a monthly account. It had just acquired exclusive worldwide distribution rights for a new controller called a ‘Soundlite’, built by two Cambridge University graduates, Ken Sewell and Paul Mardon, calling themselves Pulsar Light.

Cerebrum started offering the new Pulsar range in its price list, together with some new projection effects from Optikinetics. These included the very first set of 3” effect cassettes, which had a recommended retail price of £20 each (without projector or attachments), while a Tutor 2 with liquid wheel was priced around £125.

With mobile discotheques starting to take a real interest in lighting as well as sound equipment, the early companies (including John Jeffcoat’s Son et Lumiere, formed after he split from Tony Gottelier) were now reporting good business, while Optikinetics’ response was to move from its Hatfield farmhouse commune to business premises in Luton.

There have been opportunities for Lethbridge to dust off his effects subsequently: the famed High End bash in 1994 and a light show for a ’60s disco at his daughter’s school, when he scavenged half a dozen Tutors from people in the industry, placing four in a square and using glass liquids — sequential slides to create the illusion, for instance, of a bird flying back and forwards.

In addition, 30 years after the original (and defining) 14 Hour Technicolour Dream at Alexandra Palace, there was a reunion at the ICA called The Recurring Technicolour Dream, with John’s Children and Arthur Brown, in which John Lethbridge was involved.

He remembers that having kept his old original inks and slides, at the ICA he gave them away, figuring he’d have no further use for them.

The evening was a defining moment in other ways, since the second ever Technicolour Dream — also held at Ally Pally and called the Love-In Festival — was the first time John Lethbridge had ever witnessed the spectacle of a light show.

|

. |  |

TPi

Photography courtesy of John Lethbridge

Thanks to Pooter’s Psychedelic Shack and Neil Rice

(www.pooterland.com)

NEXT MONTH:

Neil Rice & the 1994 High End spectacular

NEIL RICE:

Riding The Legend

Of Dantalian's Chariot

After visiting the Windsor Jazz & Blues Festival in August 1967, Neil Rice's direction

in life was shaped . " I was 17 and looking forward to seeing The Pink Floyd for the first time - but they were a no-show, " he recalls .

"Then Zoot Money's band, Dantalian's Chariot, came on and the light show was spectacular. The impact for an open-air festival was amazing - they did this, blinding colourful light show, finally

depicting a large pair of naked breasts, a slide which was then set fire to with a blow torch."

And so Rice drifted into light show generation - first as a hobby and later a profession. " In those days, projectors were 'sit-up and beg' Aldis devices, with the delicate photographic filament lamps, which you had to switch off and allow to cool."

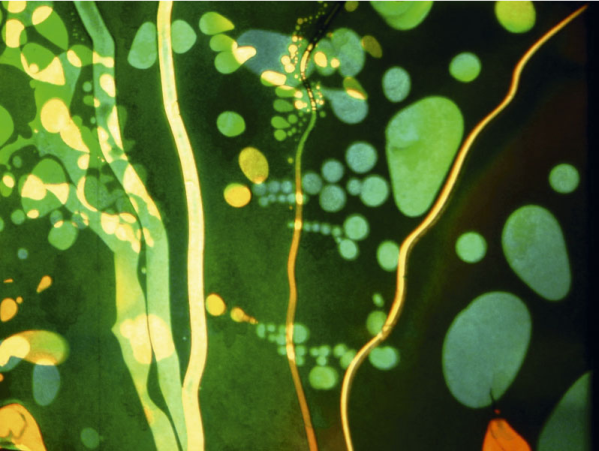

Liquid effects were generally provided by the use of wet or oil emulsion slides. "We would project liquid slides which were handmade," recalls Rice. "We would take a bag of slide glasses and bottles of coloured inks and dyes, dropping a blob in the middle and putting another slide on top , and then spreading it. The sandwich could run up to four Ievels thick .The slide was pushed into the gate of the projector, and the heat of the lamp caused the liquid to boil.

Rice, in fact, customised the projector so that with the aid of a lever he could lift the heat filter like a portcullis, removing it entirely. The projectors were all metal and glass so I was also able to use a gas blow lamp to boil the slide he explains.

Neil Rice's early lightshows were Ono Yasumaro’s Illumination Factory (run with Ken Smith), and later Infusoria Five Acre Light Show. But the first turning point came when he discovered Krishna Lights in Goodge Street. “Krishna I first encountered in 1968 via an ad in International Times, and trooped up to meet Jimmy Doody and Keith Canadine. They were the first people making lightshow equipment commercially in the form of the liquid wheel."

As stated in a previous Chronicle instalment, among the continuum of lighting vagabonds who passed through Krishna Lights in the early days was the now veteran production manager

Robbie Williams. Rice became a customer, a friend and then an employee, throwing up a promising career in architecture.

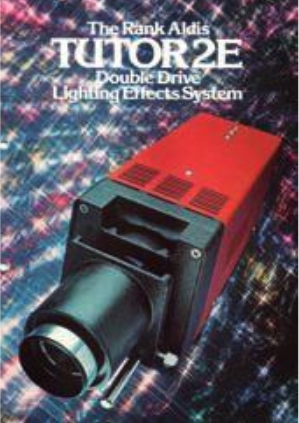

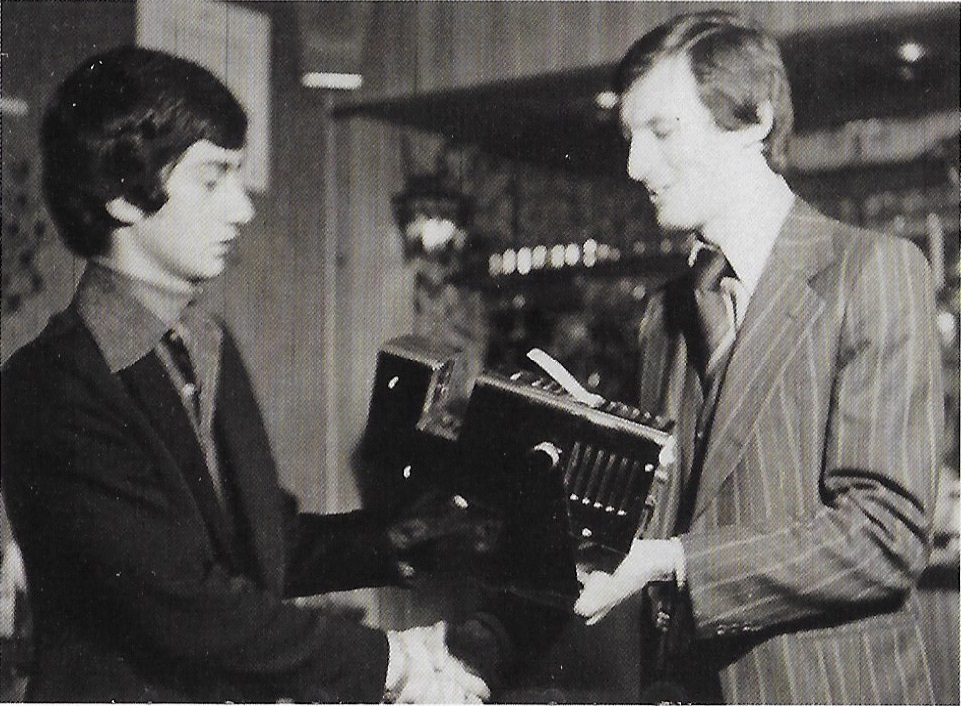

Below: L-R Neil Rice, former Badem now Plasa chairman Jim St Peter, the late Keith Canadine of Optikinetics and David Neale then of Disco International at the 1977 exhibition at London’s Bloomsbury Hotel.

Krishna Lights was also where Rice first encountered the Tutor 2 – Rank Aldis' replacement for the Tutor 1. "Krishna were buying in bulk from Rank in Brentford and adding a motor to turn the disc," says Rice. Meccano played a large part in early light show projectors!"

Apart from using 'sit up and beg' style projection to run wet slides, Rice remembers his use of strobe as being a high-speed chopper wheel in front of a photographic flood lamp in a box - an effect shamelessly borrowed from Dantalian's Chariot. Rice then discovered the Service Trading company, run by Ted Gilby in London 's Chinatown, which was offering electronic strobe kits and Xenon flash tubes.

"The only thing you then had to do was put it in a box. I subsequently offered that strobe second-hand for sale in Melody Maker and John Lethbridge came round in a Triumph Herald open

top with a gaggle of hippies." He thus became aware of Lethbridge's light show which performed at places like Kingston Pally, Ewell Tech and Eel Pie Island where as Rice's patch was further south into Surrey - Farnham, Guildford Civic Hall and Surrey University.

The Tutor 2 had originally been designed as an industrial and educational projector to be used in the classroom and as an aid to teaching . As designed, it was not suited to the dusty, vibrating and 'in transit' environment of the mobile DJ and was prone to mechanical failure. The fan and motor assembly were particularly prone to dropping out and melting, devastating the projector centre section.

By the middle of 1977, Rank Aldis had carried out its own modification and introduced the Tutor 2E at the International Lighting Exhibition in the States. The modification allowed it to accept a wide variety of attachments to alter the projected image and was designed to meet the needs of effects lighting at exhibitions, discotheques and in hotel foyers.

Unlike its predecessor, the Tutor 2 featured a quartz halogen lamp (24V 250W) - a new light source which was far more rugged than the 500W and 1OOOW Tutor 1s.

Deciding to replace his old Aldis projector with a new Tutor 2, Neil Rice again ran an ad in Melody Maker for "four Aldis projectors, doctored for light show. £25 each or £95 the lot ". He returned home that evening to find that the telephone had been burning red hot.

"Not that commercial bells rang immediately but it didn't take me long to realise that there was more money to be made from selling, rather than using projection," Rice admits.

At that time, Phil Brunker was living in South Norwood buying projectors that were made in Eastern Europe and making his own liquid wheels. Both Brunker and Krishna Lights had a common customer in Peter Cutchey, later to run Light Fantastic in New Haw before seeking his fortune in the States.

At Light Sound Studios in Acton, where Henry Fenton-Weill had succeeded his business making guitar amplifiers with a new lighting focused-company, Cutchey was instrumental in introducing Rice to Keith Canadine, who with Phil Brunker were to form Optiklnetics on November 27 1970.

Cutchey later left Light Sound Studios and formed Image Lighting and, later, Lights Fantastic. Another significant, but much later arrival on the scene was Pluto, founded by former Krishna man Richard Millington, and their interchange cassette system would later take the art of discotheque lighting still further. Meanwhile, at Krishna Lights, Tutor 2s and liquid wheels were being sold in small quantities as major works of art (liquid wheels at that time were fetching £15 each). "The fact that I was earning £10 a week puts that into perspective," says Rice.

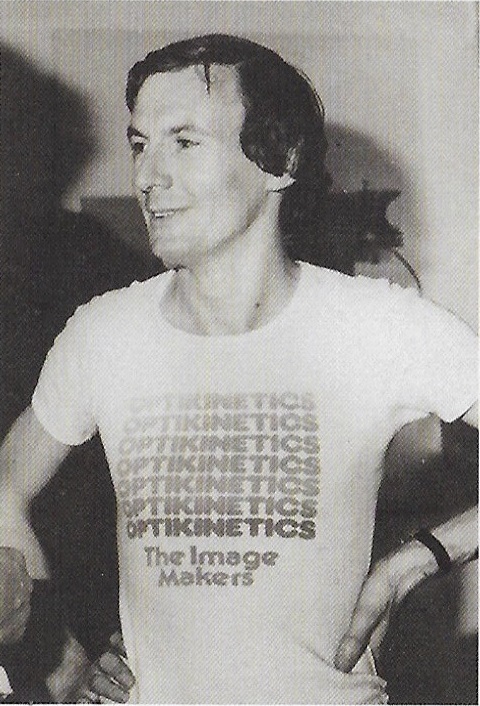

Below: In 1977, Neil Rice presenting the 10,000th Solar 2S0 projector; sporting some Optikinetics branding in the following year.

NEW FORMS

Other major lighting developments at that time aside from liquid wheels - were polarising slides, and then the effect cassette, which Rice takes credit in developing. "I had seen '60s op artist, Bridget Riley's radial moiré effect on the console of the Starship Enterprise on Star Trek when it was in black and white," he says. "I had cobbled this effect on to a projector using a large ball-race and introduced it to Krishna Lights - only to see it commercially adapted into what subsequently became the effect cassette." Ironically, that product is one of the mainstays of Optikinetics to this day, along with rotating moiré patterns and the 6"picture wheels.

Rice, too, draws the differentiation between the American and British approach. This was significant, he says . "We used vertical wet slides whereas the US favoured glass bowls and overhead projectors, only using slide projector for projecting graphics and polarising slides."

To supplement his meagre income, Rice' started selling polarising slides to Peter Cutchey, since Cutchey himself had moved on to Image in Denmark street (an apocryphal industry story suggests that Cutchey later invented the beam effect while perched on an outside toilet. He was then smoking and exhaled into the incoming rays of sunlight passing through an air brick).

Optikinetics, meanwhile, set up its commune on Barbara Cartland's estate at Camfield Place in Essendon, near Hatfield. With Krishna Lights based in W1, it was very much a London-based scene, and early customers included Exciting Lighting, run by Mickey Tenner (who later went on to Intervision), and Rolf von Branzig. Another customer was Mike Sutin, of Sutavision, purveyors of lighting to the London clubs, who later went on to develop projection ideas with Concorde Lighting.

While Krishna had focused its attention on projection, Exciting was concentrating more on complete schemes, with projection and control equipment.

Below: A Dynamic kaleidoscopic effect, a slide hand painted by Neil Rice’s wife Sally, and a vintage hand painted slide of a Hayward Gallery psychedelic scene.

"We invested in a Transit and capitalised the company with £500 - £300 of which went into advanced rent, " remembers Rice'." The typical cycle was getting into the transit and going to Brentford – to Crouzet to buy the motors – and Rankins in Clerkenwell to buy the glass disks. We would then go on to John Bell at Croydon, a big emporium of medical aids, to buy syringes in which to pack the araldite to seal the liquid wheels. "Then we would come back to the farm, make it into a saleable product, and drive back into London, collecting cash from our resellers before going round to our suppliers to source the next batch of components."

When Tony Gottelier and John Jeffcoat formed Meteor Illusion, and opened their showroom in Carter Lane in the City, they took on exclusive distribution for Optikinetics.

It was Colin Cadle who then introduced Gottelier to Colin Hammond, who provided the necessary capital for the business, and effectively replaced Jeffcoat. This marked the start of Meteor Lighting and its famous showroom in Chiswick. However, it was starting to become easy for anyone to buy a projector and bolt a motor on, and so Optikinetics decided it would be more profitable to sell the effects to attach to these projectors.

Rice remembers an order for 100 liquid wheels from Meteor Illusion and getting Rankins to supply

6" squares of glass. They then made a square liquid wheel which they put on top and delivered to the startled company- on April Fool's Day!

By now, rock bands were starting to become supergroups and playing much larger venues.

"You couldn't get away with low power projectors anymore as they started using higher powered

theatre lighting, such as Strand's Pattern 23s. Then fortuitously the mobile discotheque industry took off and adopted effects projection."

It 'should be stated that Optikinetics had spent the first two years converting other equipment – but completely customising it to accommodate the motor and the liquid wheels. "This seemed silly, so we asked Rank Audio- Visual if they could make a purpose effects projector for our industry. They replied that they’d looked at the market and decided it was only going to last five years... so our hand was forced into designing the solar 100.

"We'd always had to go on bended knee with cash to get product out of Brentford anyway, and

when Rank finally sent a salesman to visit us at the farm we discovered that they had lost 70% of their light projection business with us pulling out. "

A lot of parallel lines were being drawn in the early 1970’s. Rice soon met Peter Wynne-Willson at Krishna Lights and was invited back to the famous Cambridge Circus flat.

By the mid 70’s the scene was awash with lighting projector manufacturers. They included Project Electronics and Lightomation, with Andre Mussert and Alan Pinnington – although the company had originally been started by Frank Dawe, who had earlier made industrial strobes under his company and Dawe Instruments.

Whoever had guided Optikinetics direction had certainly read the signs well – for by the end of 1976 the company had sold 10,000 Solar projectors

Thanks go to Neil Rice, and a big thankyou to Jerry Gilber for permission to reproduce his work.

Lord of Light : Jonathan Smeeton

By Jerry Gilbert

|

|

Jonathan Smeeton

Part 1

Jerry Gilbert’s celebrated Chronicle series continues with a two-part exploration of the life and career of lighting design visionary Jonathan Smeeton.

Part One:

The Legend of Liquid Len.

On March 8 2009, Hawkwind surrogate, The Hawklords were set to turn back the clock 35 years and play a one-off reunion in honour of the late English graphic artist, Barney Bubbles.

Fittingly, this would be a Space Ritual 2009 show, inspired by Bubbles’ artwork for the original 1973 album and Robert Calvert’s space-rock opera show, with a nod to the artist’s bleak monochromatic concept for the Hawklords’ 25 Years On production later in the decade.Equally appropriate was the fact that the extravaganza was being promoted by John Curd, whose Head Records label had enshrined the whole spirit of what was taking place around Notting Hill and Ladbroke Grove nearly 40 years ago; which is where this story begins.

According to Wikipedia, “The Space Ritual show [of December 1972] attempted to create a full audio-visual-cerebral experience, representing themes developed by Barney Bubbles and Robert Calvert entwining the fantasy of Starfarers in suspended animation travelling through time and space with the concept of the music of the spheres.” In other words, a lunar safari.

The ringmaster in this travelling circus (or ‘Hawkestra’), which included sci-fi writer Michael Moorcock and the body-painted, curvaceous and entirely naked ‘exotic dancer’ Stacia [Blake], was one of the first real celebrity lightshows, Liquid Len & The Lensmen.

As a music journalist, I attended many Sunday afternoon Roundhouse Implosions (the name coined by promoter John Curd, Caroline Coon and DJ Jeff Dexter) back in the day, diving into the brutal immersion tank created by Len’s battery of unregulated strobes and 1000W projectors.

For me, that throbbing, pulsating juggernaut in the psychotropic/psychedelic Roundhouse rotunda, mixed with Bubbles’ gothic sci-fi graphics and fascist symbolism, remains indelible. Whether you were acid-charged or not (and many were), by the time this band of hippy vagabonds had launched into their third number you’d swear you were seeing orbs of light.

Subjected to this relentless blitz the band didn’t seem so much galactic warriors teetering on the edge of the astral plain, as crash test dummies.

It was probably too much to expect that Hawkwind co-founder Nik Turner — in attempting to recreate the zeitgeist 35 years on — would be able to lure the cosmic lightlords back into the fray, despite promoter John Curd billing an appearance by ‘Liquid Len & The Lensmen’ on the posters. But the promoter knew the patina of a reformed Hawks (the Wind or Lord version) would be too irresistible a prospect for many of their old fans.

In fact the legendary LD (real name Jonathan Smeeton, who for many years has been domiciled in the States) had agreed to rent his name for the occasion. Would he be making an avatar-like appearance perhaps? Nik Turner confirmed not. “The Hawklords’ lighting will be tailored to the Liquid Len & The Lensmen blue-print,” he said, “with Jonathan Smeeton’s guidance, collaboration and blessing. Expect the unexpected.”

Suffice it to say that Smeeton had agreed to cede his once famous stage name, “since I haven’t used it since Reading...”. This was a reference to the Reading Festival of 1975 when he formally quit the band, along with Stacia. However, Hawks fans still harboured hope that the great man would be controlling the whole enterprise via robots from his Fortress of Solitude at Leipers Fork, 25 miles outside of Nashville.

RE-DISCOVERING ‘LEN’

The gravitational pull to track down Jonathan Smeeton gathered momentum after I stumbled into Nik ‘Thunder Rider’ Turner, the band’s original sax player, at a Charisma Records reunion in Soho shortly before Christmas.

Three months ago I knew nothing about the Roundhouse event but the seed was still germinating after TPi editor Mark Cunningham, with righteous indignation, asked why Chronicle hadn’t yet devoted a chapter to this scion of light. So instead we’re devoting two.

Then I discovered one of my chums, Paul Gorman had just produced a biography on Barney, who tragically took his own life in 1983, and all the cosmic energy seemed to coalesce.

Smeeton’s early experimental work — with Hawkwind and before — had a major influence in shaping modern lighting design. Harnessing technological innovation to his artistic vision, today his creativity remains in high demand, not only in concert touring, but the worlds of film, architecture and lecturing.

I can’t pretend to have seen Jon Smeeton prior to that Roundhouse experience and have only met him in person once — a chance encounter on the stand of LSD at [probably] the 1992 LDI Show in Dallas. And as for famous early ’70s lightshow, the only other I can recall was Joe’s Lights, who were resident at London’s Rainbow Theatre, and also became the light artists for the 1972 Bickershaw Festival.

ANCIENT OF DAYS

Jonathan Smeeton’s story begins at the legendary UFO club in 1967, two years before I arrived in London to join Melody Maker and became inducted into London’s W10 (Ladbroke Grove) and W11 (Portobello Road) musical demi-monde.

This was the holy grail of free festivals, featuring ‘People’s Bands’ (think Pink Fairies, Quintessence, Deviants) and influential management like Doug Smith’s Clearwater Productions (Hawkwind’s management) and Blackhill Enterprises’ Peter Jenner and Andrew King (Pink Floyd’s original managers).

I had experienced Dantalian’s Chariot’s spectacular psychedelic launch at the National Jazz & Blues Festival in Windsor, but nothing had quite prepared me for the Hawkwind experience several years later.

The emerging creative spirit at that time was largely incubated in the incendiary womb of the art schools (Farnham, Hornsey, Kingston-upon-Thames, etc) — all hotbeds of social unrest. It was while at art school that Smeeton built his first lightshow, which he would use at UFO and Electric Garden (later Middle Earth), featuring three 1000W projectors.

But these inventions had less to do with any ‘art school movement’ than a simple fiscal imperative. “It was sheer lack of money — it was 1967 and I needed a summer job. I found Middle Earth, a hippy night club about to open in Covent Garden who needed someone to run their lightshow... which meant fixing their projectors, learning how to boil ink and stay up all weekend long.

“Middle Earth is where it started for me. I just walked through the door, asked for a job and, became the lightshow guy... just like that!” In keeping with the idiomatic nomenclature of the day, he called his lightshow The Ultradelic Alchemists.

Apart from all-night weekend stints at the landmark venue, Smeeton also worked Friday all-nighters at UFO. “When UFO moved from the Blarney Club in Tottenham Court Road to the much larger Roundhouse [in Chalk Farm] lightshows were recruited to fill the extra screen space... and there we were.” He soon supersized his rig. Lighting artillery back in 1967 consisted of “just lots of Aldis projectors — usually, three per screen. Little by little, I acquired more and more projectors to fill more and more screen space. We all got paid by the projector so the more, the merrier!”

In this brave new world the method of projection used in the UK was to boil ink and transparent glass stain between multiple glass 2” slides using conventional slide projectors. “It wasn’t long before we added footlights, and started to use multiple slide projectors to produce crude five cell animation loops.”

The footlights, photo-floods — three (RGB) per unit — were all controlled individually from a keyboard arrangement, The Colour Organ. “There was no dim, it was just flashing and flickering. Then came slide animation using five GAF Anscomatic 500W slide projectors. Strobes were also a new effect.” It was during the summer of 1970 that Steve Winwood had persuaded Smeeton to build a show for Traffic, which incorporated for the first time that keyboard control system.

Between residencies at UFO/Middle Earth and joining Hawkwind full time, Smeeton had provided stage lighting for bands on the Notting Hill-based Island Records label like Free, Mott The Hoople and the aforementioned Traffic. “I was using mostly footlights — a hold-over from the lightshow days — and two, three, even four pipe and base towers, mostly for town hall gigs around England.”

Through ’68 and ’69, the LD spent time on the road in Europe by which time the first wave of psychedelic lighting was all but over. He turned his attention to stage lighting, adding Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart to his roster.

“The first theatrical lighting I used was rented from Strand Electric, before they became Rank Strand — Pattern 23s, 123s and, later, 232s. The Pattern 252 effects projector was also a favourite. I used them well into the ‘80s because they produced particularly good cloud effects. I also used the Strand ‘Tubular Ripple’ effect, which I still, on occasion, use to this day.”

SOCIAL NETWORK

Living in Ladbroke Grove, Smeeton knew Nik Turner, who would often convince him to turn up for their free shows with Andy Dunkley DJ’ing. Turner was at the centre of the social network in W10 and W11 — London’s own little Haight Ashbury.

He spent his time sleeping on the floor of Barney Bubbles, who was artistic director of Frendz magazine, or dossing at the Clearwater offices with future Hawkwinder DikMik, while by day delivering silk screens for the Family Dog shop, who sold hippie/psychedelic accoutrements in Blenheim Street. “I think I then moved in with [Robert] Calvert and we formed a bit of a commune.”

Starting as Hawkwind’s roadie, once Turner had picked up his sax he was immediately drafted into the original line-up, and while Dave Brock was the front-man, he became the glue that held the whole thing together.

Smeeton, meanwhile, was continuing to tour. But after losing his stage equipment in the legendary Montreux Casino fire of December 1971 whilst working with Zappa, he was formally invited by Hawkwind to form the new lightshow prior to the Space Ritual tour.

“I had heard about him and knew he was working a lot for Blackhill Enterprises and doing quite a lot of Island acts,” remembers Turner. He was always busy. He developed a style of multiple projection and had about 20 with a different image in each — like cartoon butterflies and so on.

“Ultimately I approached him about doing lighting for us because we had no regular lighting person and we were getting big for our boots. Up until then I think we used whatever lighting happened to be at the gig.”

As psych bands started to attract audiences way beyond the scope of London clubs it was Smeeton’s ability to provide ground-breaking stadium-sized shows, using mainly slides rather than kinetic wheels, which would attract the attention.

“Around the same time, supergroups arrived and so did the 1000W PAR 64 light along with the first trusses [usually crude antenna truss]. Everybody wanted big, and they paid well too. But I chose the Hawkwind route and the experience has served me well.”

Although Hawkwind manager, Doug Smith’s memory is sketchy, Smeeton’s own recollection of the metamorphosis [into Liquid Len] was that the manager had wanted a name to put on the bill: ‘Lights by......’.

“It’s a play on words, ‘Liquid Lens’ — plus I think I was reading a [space opera] book called ‘The Lensmen’ at the time. Of course I was thinking it had to be ‘Someone & the Somebodys’. A dig at Motown perhaps? Little did I suspect the name would haunt me for the rest of my days!”

So were there actually any ‘Lensmen’? Well yes, of course. The wingmen originally comprised biologist, ‘Molton Mick’ Mike Hart (who later became a veterinary haemotologist), ‘Astral Al’ Alan Day, John Perrin and John Lee. “But later, as Hawkwind became more committed to touring and travelling to the USA more often, the permanent core became myself, John Lee and John Perrin; Mike and Alan both had proper jobs.”

With John Lee contributing his 17cwt van to become Britain‘s first lightshow ‘roadie’, they hauled a 20-projector show around the increasingly large venues, to meet increasing demand after Hawkwind’s ‘Silver Machine’ had gone to No.2 in the singles chart... and the money started to flow.

What a farrago the collective represented. Liquid Len was expected to animate a scenescape comprising an exotic dancer, a poet, sci-fi writer Michael Moorcock, the audio generator work of Dik Mik and graphic sets of Barney Bubbles. Small wonder he added a pinch of nitroglycerine to the mix.

REVOLUTIONARY

The 1972 Space Ritual tour had been a landmark, but by 1974, as they embarked on the second of their three US tours in 12 months, most of the slide material had been replaced and new concepts evolved, with the band threatening to spiral out of control in the face of ever more revolutionary equipment.

From a content perspective there was little of Bubbles’ work. The main providers were Sally Vaughan, who had been responsible for the first sets of animation slides for the Traffic show back in ’70, Nick Milner, plus leading sci-fi artist David Hardy, who contributed a fund of ‘spacescape’ slides.

There was, in fact, very little integration whatsoever among the creatives, Smeeton remembers: “The band were the band, the lightshow was the lightshow; I don’t think we ever projected any of Barney’s art other than the Hawkwind double-headed Hawk logo.

“We both lived in the Ladbroke Grove area in London so we saw a lot of each other. Things were discussed in normal conversation, but we never really sat down and had a production meeting.”

Lord of Light

Part Two:

The conclusion of Jerry Gilbert’s exploration of the life and career of lighting designer Jonathan Smeeton

Although Jonathan Smeeton collaborated little with Hawkwind’s visionary graphic designer Barney Bubbles during the early Space Ritual days, they did work consciously and co-operatively on developing the visuals for the 1978 Hawklords tour, after the LD had briefly returned to the offshoot band several years later.

“Yes, I came back for the Hawklords, which seemed a good idea at the time, but Hawkwind [by then] was at a new level of madness!” recalls Smeeton. “That really was the only time Barney and I ever deliberately sat down and discussed the design. He produced a lot of film footage to be incorporated into the show and we discussed screen placement and structures — and the timing and such.”

It was to be projected on screens suspended in scaffold towers, surrounded by lights. “I finally perfected that scaffold tower design concept for the Thompson Twins in the mid-’80s... minus the film loops,” he remembers.

On tour, Smeeton generally roomed with his old friend, Hawkwind co-founder Nik Turner. “This was probably because we shared fairly quiet lifestyles,” says Turner improbably.

But one incident in Nashville in 1973 was to become a defining paradigm in the Hawkwind hagiography. Turner takes up the story. “We played a concert in this club and the local promoter also managed of a lot of porn houses. Afterwards we were hanging out in the manager’s office when these hillbillies rode in on choppers. They had this tetra-hydro-cannabinol (THC) — which is the essential component of cannabis — in crystal form. When you snort it, it turns you to rubber — it was outrageous.”

From there they went to a skating rink when suddenly the roof started shaking. “It was like, everyone lie down on the floor, there’s a tornado happening. Comet Kohoutek was also in the cycle and you didn’t know if you were actually experiencing it or whether it was part of the trip. When we got back to the hotel half the roof was gone and all the windows had been blown out of the cars and the water sucked off the swimming pool.”

Once again life seemed to be imitating art, and although it induced a positive vibe, the chemical world seemed to have mutated with the cosmological, Turner describing it like a scene from Polanski’s ‘Repulsion’.

This is a classic Hawkwind anecdote. “It was the same as Jonathan’s lightshows,” says Turner. “You just couldn’t detach it from your own reality.”

Smeeton was forever experimenting with new effects, Turner remembers. “Like the rainbow strobe he developed, using primary colours and sequentially operated to produce rainbow effects — it was fantastic!” His only regret, perhaps, is that Smeeton hadn’t perfected the art of transmuting this, alchemically, into ingestible form.

However, even this may be somewhat surprising when one considers that the occupation given on Smeeton’s passport (according to Hawkwind manager, Doug Smith) was ‘Inventor’.

“In the early days, Jon and I spent a lot of time smoking ganga and had lots of crazy ideas,” says Smith. One of them was called ‘Crowd Control’. “We planned to have lots of little robots like obstacles on the ground; they would be filled with some very heavy weights and patrol the audience — and when people got silly they would start nudging their legs.

“Jonathan was very into drawing and developing things — but there was a humorously wicked side. Dave Brock wanted to see how many people he could freak out — at one point there was a lot of repetitive music in the early shows and we used strobes heavily and watched the number of people being carried out.”

Before Health & Safety restricted the flash rate of strobes to four flashes a second, anyone with photosensitive epilepsy could find that the rapid frequency of stroboscopes triggered a seizure.

Hawkwind were not alone in this regard. Paul Brett from Elmer Gantry’s Velvet Opera remembers their band being plastered all over the national press after colleges and universities banned their use of strobes, following the over-zealousness by their LD Ron Harwood. “Strobe lighting has a dangerous hypnotic effect upon audiences, particularly on girls,” ran the article.

After the royalties from ‘Silver Machine’, gave Hawkwind more money to play with, the lighting was placed more in Smeeton’s hands and presented properly on stage. “We had monkey rigs with PAR 64s and we started building the footlights,” Smith recalls.

Another member of Hawkwind’s band of technical support gypsies and creatives, Gerry Fitzgerald remembers all kinds of ideas that had to be aborted for technical space reasons — a collapsible 32’ eagle for the Space Ritual tour being one that would have seriously interfered with Smeeton’s projection. Other stillborn ideas were the attempt to pump dry ice downwards as a projection screen — but after a similar attempt at the Farnborough Air Display ended in explosion, it was mothballed.

“There was also the escapade with soap flakes,” says Fitzgerald. “A couple of roadies with a big box of Lux soap flakes were to be dribbled down and picked up by Jonathan’s UV and strobes. But at the Rainbow, there were these two big fans and by the side of the stage the mains switch for the fans. All a roadie needed to do was kick it and accidentally switch it on.”

Sure enough that is precisely what happened — and as the soap flakes were gently drifting down these huge fans kicked in on full power, sending the soap flakes into turbo mode (unwittingly creating the first audience blinders perhaps?) “But no-one seemed to bother,” said Fitzgerald, “they just felt that... well, it was Hawkwind.”

THE MIDDLE STAGES

In August 1975, Hawkwind had headlined on the first night of the Reading Festival, which proved to be their last gig with Jonathan Smeeton. His work with the band would lead him to even greater things although the immediate aftermath was hardly creative.

The music industry was arriving at a fork in the road — disco was spiralling off in one direction, punk in the other, with the spectre of the ‘supergroups’ and prog-rockers hovering over it all. Ironically, I was working in the indie band hotbed of West London in 1976 — a stone’s throw from the old Clearwater offices — but about to launch a disco magazine!

“Punk had a total disregard for everything, and the staple for supergroups was just huge rigs for no other reason than being bigger than the previous rig,” states Smeeton.

By 1982, Gail Colson, manager of former Genesis frontman, Peter Gabriel, had recruited Smeeton, which provided him with a baptism for the new Vari*Lite — launched by Showco the previous year on Genesis’ Abacab tour.

Smeeton used 16 VL1 heads on the Gabriel tour. “It was a very big deal at the time, me being an independent and Vari-Lite being so incredibly secretive about everything. For a short time Vari-Lite had the monopoly on ‘new’.”

Colson had been one of most understatedly powerful women in the music business when I worked at Charisma Records between 1974-76 (at a time when the company also owned ZigZag Magazine).

Although Tony Stratton Smith had started the label she was unquestionably the power behind the throne. By the late 1970s, however, Charisma’s best years were behind them, and Hawkwind’s arrival on to the label in 1976 helped to galvanise it and keep its prog-rock roster alive.

A 10-year collaboration with Gabriel was followed by stints for Smeeton with Paul Simon, Journey and the Thompson Twins. “Without a doubt I enjoyed my Hawkwind reputation for a long time afterwards,” he acknowledges.

With Gabriel at the helm, Genesis had earlier immortalised Jonathan ‘Liquid Len’ Smeeton in their song ‘The Battle Of Epping Forest’ in the lyric ‘His friend, Liquid Len by name, of wine, women and Wandsworth fame’.

One could speculate that Hawkwind’s 1972 ‘Lord Of Light’ might also have been a nod in his direction.

Since then, Smeeton’s creative vision has resulted in some of the most original stage productions in today’s music and TV business — a legacy of the expertise he gained working with video at BBC Television Centre in London.

“Just getting into the BBC was breaking barriers back then,” he says. “‘Top Of The Pops’ was run by a load of old conservatives who had never recovered from the massive and rapid change in ‘pop music’. They still thought Muriel Young was cool and that kids should watch more ‘Blue Peter’!”

His good fortune was that Pete Drummond, a popular BBC radio DJ (who along with John Peel was championing the new counter-culture), lived upstairs from him. The long-time presenter of ‘Radio 1 In Concert’, Drummond had just become the anchor man for the new late-night BBC2 programme ‘Disco 2’. “Pete got me the gig of projecting lightshows to accompany the record review segment,” Smeeton recalls. “Soon I was lighting the live act segment before the programme became ‘The Old Grey Whistle Test’. Finally, ‘Top Of The Pops’ recruited us to flash their lights, by which time it was truly old hat! But I did learn to light for TV, sufficiently to be ready for the MTV video explosion.”

Smeeton had already enjoyed a particularly busy video-making period in the ’80s with progressive visual artist Peter Gabriel and The Thompson Twins, Wham! and, later, the solo George Michael — which all proved to be heavy MTV fodder. He also produced notable touring lightshows for Yoko Ono, Lou Reed, Miles Davis and eventually Def Leppard, immediately prior to relocating to the States.

This filmic experience became invaluable with the advent of MTV and artists’ needs for both promotional and feature-length concert videos. Thus Smeeton had moved to the L.A. forest of Topanga Canyon, in order to be close to the muse.

“Everybody suddenly was making videos. As most of it was still being shot on 35mm film, Hollywood became a hot spot for shooting short-form video. At this time a lot of commercial film makers got on board and produced some very fine mini movies. There was also quite a lot of money to be made so it attracted some very talented people.”

ARCHITECTURAL

During the ’90s, Smeeton also found himself lighting many architectural interiors and exteriors “where the brief called for lighting to create mood, drama, a sense of the extraordinary.”

His first foray into architectural lighting had been way back in 1984, after being contacted by Rusty Brutsché, chairman and CEO of Vari-Lite in Dallas. “He asked me to light a building to demonstrate the effect of moving lights on walls of glass and stainless steel. Since then I’ve lit quite few buildings, mostly in a novelty fashion, not truly architectural. But music is still my core business — Nashville is a clue!”

This has now been his home for the past 20 years. “When one has spent so much time touring a place or visiting the same place over and over, it’s hard to say precisely when one moved [to the States],” he states enigmatically. “This time around? I have lived here since the late ’80s. I particularly like life in the USA. It’s near my place of work — namely, the rest of the world.”

His route to the deep south had taken him from Topanga Canyon to the beautiful Russian River, in the northern part of California, and finally a rambling ranch in Tennessee. Clearly, Smeeton likes Big Country... which is about as cosmically removed from the imbroglio of Ladbroke Grove as it gets.

Surrounded by so much beauty it’s little surprise that in his modern work regime global itineraries have become a thing of the past. “I don’t go touring anymore; I send robots and machines and clever young people who think it’s fun to live on a bus and be away for months on end.”

In fact he spends as little time as possible working. “Over the summer I teach around 30 people over about four weeks — beginners mostly. And designs can be done in days or weeks. In total I must work 10 weeks a year.”

WORKING IN THE INDUSTRY

In the 1990s, Smeeton was also a regular on the industry trade fair circuit, mostly designing exhibition lightshows for Martin Professional. “At a time when I was looking for an alternative to Vari-Lite I found Martin, or rather they found me.

“They then asked me to design their trade-show stands and lightshows for SIB [Rimini], PLASA and LDI. It was all rather good fun — creating lightshows for the sake of lightshows — but they also produce some pretty fine equipment.”

As production designer to some of the greatest names in music he has always seen explaining complex lighting techniques to lighting directors as part of the job. Thus, the obvious extension to this was to start his own school, offering regular workshops.

At the same time he has also dived headlong into the world of light/video convergence and content lighting to create multimedia, pixel-driven shows. In fact, he is currently working on a multi-media event called In Search of Space (the ghost of Hawkwind still haunting him) — along with a couple of stage play productions.

“The wheel has turned full circle for me,” he muses. “I’ve never had a difficult time getting anything on the screen, the hard part is getting the right thing on the screen at the right time.”

As he completes his fourth decade in the business, Jonathan Smeeton continues to show how in demand he is from the emerging generation, by pulling a contract that should have made him as happy as a clam. When I was in Florida last Christmas, the FM airwaves were dominated by the songs of beautiful 20-year old country singer, Taylor Swift. She has subsequently crossed over into mainstream and mega-stardom, and is currently on tour... with Smeeton as her production designer and director of creativity.

And so the road, it seems, goes on forever. If Liquid Len & The Lensmen had provided the platform for the launch of an outstanding career in lighting invention, what had it been that characterised those early lightshows to make them so special?

“Me,” came the unequivocal answer. “And the totally free rein Hawkwind allowed me; plus, of course, Douglas Smith who really held it all together and believed it could all happen.”

TPi

Photography: The TPi Archive, BBC and courtesy of Jonathan Smeeton • with acknowledgements to www.starfarer.net • Paul Gorman’s book, ‘Reasons To Be Cheerful: The Life and Work of Barney Bubbles, is published by Adelita.

Jonathan Smeeton’s website: www.robotsforpeace.com

Thanks go to Neil Rice, and a big thankyou to Jerry Gilbert for permission to reproduce his work.

Copywrite info:

This page and links contain copyright material please seek the owner or author of the material for the right to copy in full or part any of the information or imagagery included.

Copyright © M.Ginda 2018-2020 (content owners copyright may be shown in text on the page above. Do not copy content)